In 1879 silver was discovered in the eastern Empire Mountains of Arizona and the claims were held by John T. Dillon. According to Ed Vail, author of The Story of a Mine, one of the mines and the little town that sprung up nearby got their name from remarks made by Dillon when he signed the recording papers with Vail’s brother Walter in 1881.

In 1879 silver was discovered in the eastern Empire Mountains of Arizona and the claims were held by John T. Dillon. According to Ed Vail, author of The Story of a Mine, one of the mines and the little town that sprung up nearby got their name from remarks made by Dillon when he signed the recording papers with Vail’s brother Walter in 1881.

Walter asked him for a name and Dillon said, “Well, the mineral foundation is almost a total wreck,” alluding to the fact that it was located beneath a quartzite ledge that looked like a total wreck. The name stuck and on August 12, 1881 a post office was established.

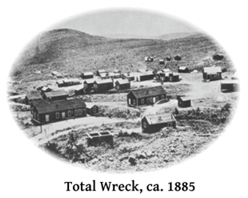

The Los Angeles Times reported in 1882 that the appearance of the town, however, had nothing to do with its name: “The town of Total Wreck has no appearance of a wreck. It is a thrifty, neat-looking village, the streets laid out at right angles. The main street is named Dillon street in honor of the discoverer of the mine, and the first to discover minerals in this district.”

The Los Angeles Times reported in 1882 that the appearance of the town, however, had nothing to do with its name: “The town of Total Wreck has no appearance of a wreck. It is a thrifty, neat-looking village, the streets laid out at right angles. The main street is named Dillon street in honor of the discoverer of the mine, and the first to discover minerals in this district.”

By that time, the town had two stores, two hotels, a restaurant, five saloons, a carpenter, blacksmith, butcher, brewery, several Chinese laundries and over thirty houses with about two hundred residents. The town was fairly well organized with a deputy sheriff who could muster a posse of ninety men within an hour of any sign of trouble from rowdies or Indians.

On September 7, 1882, the Tombstone Weekly Epitaph reported that the townspeople were overjoyed to have received telegraph connections with the outside world. The Epitaph predicted that Total Wreck was “destined to be one of the most prominent mining camps in the Territory.”

In late November of 1882 one of the local businessmen, E.B. Salsig, was a victim of an attempted assassination by a man named John Drummond. According to the Tombstone Epitaph, Drummond had a reputation and was well-known to the residents of Tombstone. The two men were quarreling over Drummond’s interference with the sale of one of the mines in the district. Mr. Salsig apparently expressed an opinion that Drummond didn’t care for.

Drummond visited the store of Salsig &Sifford and called Salsig out on the street to have a few words, “applying to him epithets which most men resist.” Salsig was insulted and hit Drummond, only to have a revolver drawn on him and then shot three times by Drummond. The first shot resulted in only a flesh wound, while the second went through a wallet and bundle of letters, causing the lead ball to drop in Salsig’s pocket; “but for this it might have produced a fatal wound.”

The legend has oft been repeated that the love letters in his pocket saved Salsig’s life and he later married the woman who had penned the letters. Drummond, however, was arrested and bound over for trial, the Epitaph remarking “it would be well if such characters as this Drummond could be summarily dealt with.”

In June of 1883, several Mexicans were cutting wood in the Whetstone Mountains and were attacked by a band of Geronimo’s Apache warriors. Six Mexicans had been killed and were the first to be buried in the Total Wreck Cemetery. Today there is little, if any, evidence a cemetery ever existed, however.

In 1888 another resident, a miner named James Burns, was buried there after collapsing while working near one of the mine areas. Total Wreck was isolated and too far from Tucson for a coroner to reach the town before decomposition set in. Of necessity, in those times when such services weren’t available, a jury of Total Wreck citizens was sworn in by a Notary Public to investigate the cause of death. The jury determined that Burns died of natural causes due to a sudden rush of blood to his head, as evidenced by the dark appearance of his head, neck and face.

As predicted by the Epitaph in 1882, the Total Wreck claims were quite productive – by 1884 mines in the area had produced around a half-million dollars in silver bullion. On September 13, 1884, the Arizona Weekly Citizen was boasting that “the Total Wreck and many lesser known properties are just beginning to show the silver edge of their boundless wealth, and their prospective output means unprecedented prosperity to our country,” Despite those claims, however, the mill built in 1881 by the Empire Mining and Developing Company was closed at the end of 1884. In those days, booms were always followed by precipitous busts.

Attempts were made to revive operations in 1886, but in the late 1880’s and early 1890’s, mining interests declined. The Tombstone Prospector and Epitaph reported in early January of 1891 that the Total Wreck post office had been closed. The Silver Crash of 1893 resulted in the closing of hundreds of mines all over the West, and subsequently the withering away of hundreds of once-prosperous mining towns. Total Wreck slowly dwindled away as well, and today all that remains are a few walls and numerous holes in the ground.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

E B Salsig was my Greatgrandfather