Blackwell

Sources agree that the Blackwell surname was a locational name, a place in the counties of Derbyshire, Durham and Worcestshire. It was an ancient surname, traced back to Olde English and Anglo-Saxon orgins.

The name was recorded in the Saxon Cartularium of Durham in 964 as “Blacwaelle”, according to the Internet Surname Database. An instance of the name was also recorded in Derbyshire as “Blacheuuelle” in the 1086 Domesday Book.

This locational name meant “black stream”, stemming from the Olde English word “blaec” which meant “dark-colored”, likely referring to the color of the water. The name may have also referred to someone who lived next to a “black stream”.

This locational name meant “black stream”, stemming from the Olde English word “blaec” which meant “dark-colored”, likely referring to the color of the water. The name may have also referred to someone who lived next to a “black stream”.

The spelling variations of this surname are varied and numerous, including Blackwell, Blackwall, Blackwill, Blakewell, Blakewill, Blaikewall, Blakwill, Blackville, Plackwell, Plakewell, Plackville, Blatswill and more.

Yesterday, I wrote about the early life of Elizabeth Blackwell, America’s first female medical school graduate. Following is the conclusion of her amazing story. If you missed Part I, you can read it here.

Elizabeth Blackwell: Medical School and Beyond

“With an immense sigh of relief and aspiration of profound gratitude to Providence”, Elizabeth Blackwell accepted Geneva Medical College’s invitation to enroll. Within days she was on her way to western New York. Upon her arrival she was interviewed by the dean of the college and assigned as student No. 130 in the medical department.

Although the medical program was short in comparison to today’s requirements, the task ahead was nonetheless daunting. One of the professors read her letter of introduction from Dr. Warrington, the Quaker who had advised her to give up, and then Elizabeth entered the lecture hall.

She later surmised the professor was reminding his students that a lady would grace their presence. Apparently it wasn’t uncommon in that day for students to make all sorts of crude remarks and jokes aimed at their professors. As the story goes, Elizabeth’s presence in the classroom made it more likely that her male counterparts would behave themselves.

While gradually being accepted by the faculty and her fellow students, the townspeople, specifically the women folk, weren’t as approving. In her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women, Elizabeth remarked:

Very slowly I perceived that a doctor’s wife at the table avoided any communication with me, and that as I walked backwards and forwards to college the ladies stopped to stare at me, as at a curious animal. I afterwards found that I had so shocked Geneva propriety that the theory was fully established either that I was a bad woman, whose designs would gradually become evident, or that, being insane, an outbreak of insanity would soon be apparent.

Still, however, she discovered that she was barred from certain lectures or demonstrations which were deemed too delicate for woman’s sensibilities – the reproductive anatomy lecture would not be appropriate for a lady. Elizabeth disagreed, argued her case and won the support of her fellow students.

Following her first term Elizabeth began searching for a hospital or institution where she could conduct her summer studies in practical medicine. She returned to Philadelphia and decided to study at the Blockley Almshouse. Her first assignment took her to the third floor, the women’s syphilitic department, “the most unruly part of the institution.”

The director thought her presence might have a positive effect on the “very disorderly inmates.” Instead, she was thought of as a curiosity. She made the acquaintance of the resident matron whose appearance belied her gruff mannerisms in dealing with patients; Elizabeth referred to her as Mrs. Beelzebub. She was, however, enraptured with the head physician, Dr. Benedict, whose patient and kind ministrations to his terminally ill patients touched Elizabeth.

The Irish potato famine brought scores of immigrants, many who had been afflicted with famine fever while making their way across the seas. Blockley was overwhelmed with the epidemic, but proved a valuable lesson for Elizabeth — she used her experiences and observations of that summer to later write her graduate thesis on typhus.

Elizabeth returned to school following her summer practicum and renewed her determination to complete her course of study. By this time she was more at ease and confident in her own capabilities, and even though she could have concurrently pursued a social life, she chose not to do so. In her words, “I lived in my room and my college, and the outside world made little impression on me.”

By mid-January of 1849 she was preparing to sit for her exams. On January 19 she wrote that she had passed her final examinations with flying colors, first in her class. Perhaps realizing they were about to witness a momentous event in history, her fellow students greeted her with applause. In four days she would become the first women in U.S. history to receive a medical degree.

With thankfulness to God on her mind, Elizabeth entered the Presbyterian church where the graduation ceremony was held on January 23. After all other students had received their degrees, Elizabeth was called to the platform. After receiving her diploma from the school’s president, she addressed him, “Sir, I thank you; it shall be the effort of my life, with the help of the Most High, to shed honour on my diploma.”

Keenly aware of her momentous accomplishment, Elizabeth knew that it was only the first step. She returned to Philadelphia for a short time, intending to continue her medical studies. Instead, at the invitation of a cousin, she traveled abroad in April and studied in Paris and London. Her colleagues and advisers had encouraged her specifically to consider studying in Paris where opportunities for women were more readily available. In June her post-graduate work continued as she accepted a position in Paris at its maternity hospital, La Maternité.

She began working in the field of obstetrics and had planned to become a surgeon. However, in November of 1849 while treating a baby’s eye infection, she contracted what was most likely gonorrhea (which was probably passed to the baby as it passed through the birth canal) and lost sight in her left eye. She would never become a surgeon.

After completing her term of study at La Maternité, and now blind in one eye, Elizabeth traveled around Europe for a time. Her studies at St. Bartholomew’s in London, however, presented a challenge as she noted in journal entries and letters to her family. One professor in charge of Midwifery and the Diseases of Women and Children had basically written her off, politely informing her of his disapproval of women in medicine.

While in London, one of her more pleasant experiences was a social one, making the acquaintance of Miss Florence Nightingale (although they later had a falling out). By May of 1851 it was time to consider whether it would be more profitable for her to remain in England or return to America. Encouraged by attempts in Philadelphia and Boston to found schools for women to pursue medical careers, Elizabeth finally departed England in July of 1851.

Elizabeth chose to begin her formal practice in New York, but the first seven years were “uphill work”. As a solo practitioner, with a largely empty waiting room, she began to feel isolated and in 1853 established a dispensary among the New York’s poor, near Tompkins Square in Manhattan.

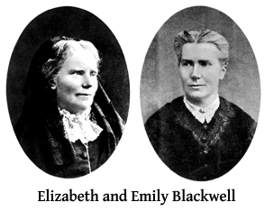

In 1857 the dispensary expanded into the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The third woman in U.S. history to receive a medical degree, her sister Emily, joined the practice. Emily’s presence lifted her spirits, her “working powers more than doubled.” While Elizabeth focused on the practice of obstetrics and gynecology, Emily handled the surgical practice.

Still, the hospital caused a stir because it was one thing for a woman to receive a medical degree, but yet another to found a hospital and purport to train other women in the practice of medicine. They had been warned that no one would lease them a facility, and they would be looked upon with suspicion purely because they were female doctors. The critics believed that without male doctors at such a facility there was no way the women could control the situation should some incident or accident occur.

Elizabeth and Emily plowed ahead, determined that their hospital would be staffed entirely by women. Perhaps to assuage the public’s doubts, the board of physicians which oversaw their operations was entirely male, all supporters of the Blackwell sisters and their enterprise.

Elizabeth traveled throughout Europe and immersed herself in social reform, specifically in areas concerning women’s rights, health issues, medical education for women and more. She traveled back and forth to London several times in the 1860’s and 1870’s, and in 1874 helped establish the London School of Medicine for Women.

She and Emily had experienced a rift in their relationship, disagreeing over the management of the hospital and medical college. In 1869 she left America behind, having become somewhat disenchanted with the women’s medical movement there, and returned to England. She worked for a time at the London School of Medicine for Women but was gradually pushed aside as a physician. In 1877 she left the active practice of medicine and continued to push for social reforms.

Like her five sisters, Elizabeth never married. She simply had no use for, nor the time to pursue a marriage relationship. She had always possessed a strong personality and could be quite critical in her views of others.

Her memoirs were published in 1895, and Elizabeth remained a professor of gynecology until 1907 when she fell down a flight of stairs. The accident left her not only physically challenged, but mentally disabled as well. On May 31, 1910 she suffered a stroke at her home in Sussex and died at the age of eighty-nine.

Her memoirs were published in 1895, and Elizabeth remained a professor of gynecology until 1907 when she fell down a flight of stairs. The accident left her not only physically challenged, but mentally disabled as well. On May 31, 1910 she suffered a stroke at her home in Sussex and died at the age of eighty-nine.

Her sister Emily died four months later in Maine on September 7 at the age of eighty-three. Their pioneering work had paved the way for wider acceptance of women in medicine. In 1915 the American Medical Association admitted its first female members.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!