Most sources agree that today’s surname is of occupational origins, perhaps referring to someone who was a mender of pots and pans (“tinner”). The earliest individuals bearing a particular surname, especially an occupational one, were usually employed in that profession. The occupational name passed to succeeding generations even if the occupational tradition was not, especially after The Middle Ages.

The Internet Surname Database disagrees with the type of occupation, believing that the name did not necessarily refer to someone who mended pots and pans, but perhaps one who sold them – a peddler. Their premise is that the name derived from the Middle English word “tink(l)er” because “they made their approach known by tinking, by either ringing or making a tinkling noise.” Another reason for their theory is that during King Edward VI’s reign a law was passed basically outlawing peddling: “No person or persons commonly called Pedler, Tynker, or Pety Chapman, shall wander or go from one towne to another . . . and sell pynnes, poyntes laces, gloves, knyves, glasses, tapes, or any suche kynde of wares whatsoever or gather connye skynnes.”

A person bearing this surname was recorded in 1244 in “The History Of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital”, but one of the first instances may have been recorded in 1243, during King Henry III’s reign, in County Somerset for Robert le Tinker. The name may also have appeared as “Tinkler” at times – Edward Tinkler was listed in the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379.

Thomas Tinker

Thomas Tinker, thought to have been the first Tinker to come to America, was a passenger on the Mayflower and made the journey because of religious persecution. Before their arrival in the New World, forty-three Pilgrims signed their names on November 11, 1620 to a document called the “Mayflower Compact” which would govern the settlers. His name is also inscribed on the Plymouth Rock Monument.

The Compact had been signed while still on board the ship and the original intent was to disembark in the colony of Virginia, but storms forced them to take refuge in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, later named Plymouth after the port city in County Devonshire.

The Compact had been signed while still on board the ship and the original intent was to disembark in the colony of Virginia, but storms forced them to take refuge in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, later named Plymouth after the port city in County Devonshire.

Thomas, his wife and son were likely English separatists who had resided in Leiden, Holland for a time to escape persecution. Thomas Tinker was a wood sawyer by trade. The names of his wife and son were not noted, recorded by William Bradford as “Thomas Tinker, and his wife and a sone.”

The journey was not an easy one and two deaths occurred before landing in Massachusetts. Sickness had already been rampant and upon arrival the Pilgrims were faced with even more challenges. Sadly, Thomas Tinker and his family all perished – “all dyed in the first sicknes” according to William Bradford. That would have occurred sometime between December 1620 and January 1621, but no specific date was recorded for the Tinker family’s death. They were likely buried in unmarked graves in an area referred to today s “Cole’s Hill”.

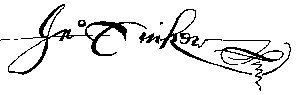

John Tinker

John Tinker was born in England around 1614 perhaps and his name began to appear in Boston records around 1635. It’s possible that John’s parents also immigrated around the same time. In 1639, while away in England, John wrote a letter to John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and enclosed a letter for his mother.

It appears that John Tinker was a well-educated man who had obtained a social position worthy of being addressed as either “Mr. Tinker” or “Master Tinker”. Records show that he was a merchant or trader as well as an attorney. John married Mrs. Sarah Barnes, a divorceé with two daughters (her husband had deserted his family), but it’s unclear when their marriage occurred.

Curiously, her divorce from William Barnes was not recorded until 1649 – and Sarah died in 1648. Following her death, the care of her daughter Mary was entrusted to Richard Cooke, a tailor in Boston and Alice was cared for by John Tinker. Some speculate that perhaps Cooke was Mary’s uncle, his wife being Sarah’s sister.

Sometime prior to December 9, 1649 John married his second wife Alice Smith (Alice signed her name “Alice Tinker” as witness to a land transaction on that date). In 1654 John was made a freeman and in 1655 was offered a sizable piece of property in Lancaster, Massachusetts in exchange for his governmental service as the town’s clerk. In 1659 he and his family removed to Pequot in the Connecticut Colony.

In Pequot John was again active in governmental as well as church affairs. Not long after his arrival the minister of the First Congregational Church in New London departed and John filled in until a new pastor arrived.

While serving as the Chief Magistrate of New London’s Court, John refused to prosecute someone who had spoken out against the King of England. Three of his fellow citizens took exception and charged him with treason, after which John charged them with defamation.

The suit went to the General Court at Hartford, but before it could be settled John Tinker died in October of 1682. The Court, however, regarded those charges as attempts to malign Tinker’s character and levied fines against his accusers. Out of respect for his reputation, the expenses of John Tinker’s illness and funeral were borne by the Colony of Connecticut.

One more Tinker story. In 1663, too long after John’s death, his wife Alice was found to be “with child.” Of course, this type of thing was not tolerated in the Puritan community and Alice had to appear before the General Court. Before the Court she shockingly admitted that the father of her child was Jeremiah Blinman, son of a former minister. Apparently, Alice only paid a fine – otherwise she could have been subjected to more stringent and obvious forms of punishment (think “scarlet letter”). Jeremiah also paid a fine in 1663.

As it turns out though, Jeremiah was not the father, but a married man by the name of Samuel Smith, a New London commissioner. Samuel deserted his wife and moved to Virginia before Alice’s baby was born – records and depositions seem to indicate that he admitted responsibility after his wife Rebecca filed for divorce on the grounds of desertion. The divorce was finalized in 1667.

Meanwhile, Alice Tinker had married another man, an attorney by the name of William Measure, in 1664. Alice, her five children by John Tinker and William Measure moved to Lyme, Connecticut soon after their marriage and remained there until their deaths.

What happened to the illegitimate child? Sarah Tinker was born in Lyme in 1664 (whether before or after Alice’s wedding to Measure is unclear). A record exists in the land records of Lyme listing Sarah as the “daughter of John Tinker”, entitling her to an allowance of land equal to that of any heir of the land’s original owner.

Sources:

Descendants of James Stanclift of Middletown, Connecticut and Allied Families, by Robert C. and Sherry [Smith] Stancliff

The Ancestors of Silas Tinker in America from 1637, by A.B. Tinker (1889)

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Sarah Tinker married Jonathan Hudson, of Shelter Island, LI, NY, 17 Jan 1686, Lyme, CT. She died 11Sep 1746, Shelter Island.