The subjects of today’s article were not only “mothers of invention” but also made a bit of naval history as well, contributing to the Union’s cause during the Civil War.

The subjects of today’s article were not only “mothers of invention” but also made a bit of naval history as well, contributing to the Union’s cause during the Civil War.

Sarah Mather

Unfortunately, for history’s sake, little is known about inventor Sarah Mather. One source believes her to have been married with at least one daughter. There don’t appear to be any records of other inventions by Sarah Mather (except an improvement on the first). However, her submarine telescope was an important naval innovation.

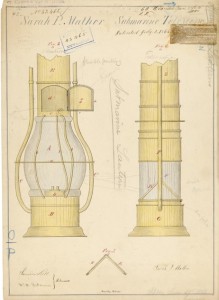

On April 16, 1845, Brooklynite Sarah Mather was granted a patent (US Patent No. 3995) for an invention she called a “submarine telescope” – an “Apparatus for Examining Objects Under the Surface of the Water”.

On April 16, 1845, Brooklynite Sarah Mather was granted a patent (US Patent No. 3995) for an invention she called a “submarine telescope” – an “Apparatus for Examining Objects Under the Surface of the Water”.

The nature of my invention consists in constructing a tube with a lamp attached to one end thereof so to be sunk in the water to illuminate objects therein, and a telescope to view said objects and make examinations under water. . . .

It will at once be obvious that the above named lamp and telescope can be used for various purposes, such as the examination of the hulls of vessels, to examine or discover objects under water, for fishing, blasting rocks to clear channels, for laying foundations or geological formations, the lamp being used for lighting the objects while inspected by the telescope.

Primarily, her invention was used to examine a ship’s hull without having to remove it from the water. On July 5, 1864 she was awarded US Patent No. 43465 for an “Improvement in Submarine Telescopes”. With the beginnings of submarine warfare during the Civil War, her invention was also useful in detecting Confederate underwater activity.

Martha Jane Hunt was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1826. After her mother was widowed, her family moved to Philadelphia sometime in the 1830’s. By the age of fourteen, Martha, in her own words, was “unusually tall and mature in appearance for my age.” She attended school and studied hard. One summer day she was attending a picnic in the park and met nineteen year-old inventor Benjamin Coston.

His prowess as a skillful inventor was well-known in Philadelphia. He had been working on a “submarine boat or torpedo” which could operate underwater up to eight hours without resurfacing. The air needed to survive underwater was a chemical process which he had also invented. She was obviously impressed with his skills as an inventor, not to mention his handsome features. In her autobiography, A Signal Success, she remarked, “to tell the truth, I was a little too much in awe of his genius to be quite at my ease with him.”

They began to spend a great deal of time together, he assisting with her school work, especially in mathematics, grammar and history. As long as he remained in the city she excelled, but during his absences her grades suffered. She began to depend on him and, needless to say, she was falling in love with Mr. Coston, and he with her. Her mother was shocked to hear from Benjamin that he was in love with her “baby girl”, but agreed to allow their marriage when Martha reached the age of eighteen.

Benjamin’s work had caught the attention of Admiral Charles Stewart, a.k.a. “Old Ironsides”. The admiral urged Benjamin to join the navy and arranged a meeting with the Secretary of the Navy. Benjamin received an appointment as master in the service of the Navy at the Washington Navy Yard. Realizing that they would be separated for an extended time, and having grown so fond of each other, they decided to elope.

With her sister (Nellie) and Nellie’s fiancé Tom Blair as witnesses:

We proceeded at once to the house of a minister, unworthy of the gospel he preached, and willing for the sake of an extra fee to ask no embarrassing questions and agree to make no revelations. . . . and in a few moments it was over, and I, a sixteen-year-old girl, a wife.

Because of Benjamin’s assignment to the Washington Navy Yard (instead of a two-year scientific expedition at sea), the young couple relocated to Washington, D.C. After four years of marriage they had two young sons. Benjamin’s worked in a pyrotechnic laboratory where he developed and tested rocketry for the government. Although his work was well received, Benjamin and the Navy were at odds in regards to promotions and credit for his work. He resigned and accepted a position as president of Boston Gas Company.

The family continued to grow after they moved to Boston. After the birth of their fourth son, Benjamin was called to Washington on business. As he was returning, he became seriously ill and three months later died. Martha returned to Philadelphia to live with her mother, but not long afterwards her baby son Edward became ill and died as well.

The tragedies continued as her mother also died a short time later. Martha, always close to her mother, was devastated, remarking “I had lost both my anchor and my pilot, and was at the mercy of unknown seas.” As she was dealing with multiple tragedies, the family’s finances had not been tended to properly and Martha realized that her source of income from Benjamin’s business was depleted. At twenty-one she was penniless with three small children.

One rainy afternoon in November she began going through some of Benjamin’s papers, some of which consisted of his notes for unfinished inventions and chemical experiments while working with pyrotechnics for the Navy. She came upon a large envelope which contained a detailed plan for signals which could be used at night much like signal flags were used during the day. Each signal was numbered and a certain fire color assigned to each one, corresponding to colors used by signal flags during the day.

She began corresponding with Navy officials, trying to find someone interested in the perfection of Benjamin’s plans. Some of her husband’s naval co-workers assisted her efforts to develop flares for testing. The tests, unfortunately, were utter failures. In the meantime, tragedy struck again when her second son became ill and died – just as her initial communication efforts were rebuffed. Still, the Secretary of the Navy encouraged her to continue.

Martha pursued the task, giving over the care of her two remaining sons to friends so she could dedicate herself full-time to the project. It would take years of working with chemists to perfect the flares, as well as find a manufacturer. The task was arduous, but they finally were successful in developing a pure white and vivid red light. A third color was needed, however.

In August of 1858 Martha was in New York City attending the celebration of the first transatlantic telegraph cable being laid. A fireworks display gave her the idea that a pyrotechnics company might be able to help her develop the third color. She inquired with several firms, requesting either a blue or green color. They worked together for several weeks and finally in February of 1859, a naval review board gave her a favorable report. On April 5, 1859, Martha Coston was granted US Patent No. 23,536 for a pyrotechnic night signal and code system. Benjamin, however, was listed as the inventor and she as the administratix.

For the next two years, the Navy tested the new system around the world with satisfying results. The perfection and successful testing couldn’t have come at a better time. After Fort Sumter, Congress passed a funding bill and Martha and her partner immediately began production of the Coston signal flare – they sold one million flare signals during the Civil War. The signals were, of course, important tools to issue orders before and during battles. For the Navy, however, it allowed them to identify whether an approaching vessel was friend or foe, since the Union exclusively used the signals.

So successful were the Coston signal flares, David Dixon Porter, a Mississippi River squadron commander, would later write:

at night the signals can be so plainly read that mistakes are impossible, and a commander-in-chief can keep up a conversation with one of his vessels distant several miles, and say what is required almost as well as if he were talking to the captain in his cabin. This was the case in the Mississippi and also in the North Atlantic Squadron during the war, where we read hundreds of these signals (nay, thousands), which were frequently kept going all night long.

Martha continued to improve the device and in 1871 received a patent for a “Twist Ignition” device. Coston Signals were used on April 17, 1912, the fateful night when the Titanic sunk. Naval and Coast Guard services utilized the signals until marine radios came into usage in the 1930s.

Martha continued to improve the device and in 1871 received a patent for a “Twist Ignition” device. Coston Signals were used on April 17, 1912, the fateful night when the Titanic sunk. Naval and Coast Guard services utilized the signals until marine radios came into usage in the 1930s.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

My great grandmother is Sarah Mather married George Mather is this the same woman I know of three children Ernest Dolly and Erskine

I could only find possibly one daughter and she lived in Brooklyn. Does that match?

Laurie, my name is Sandra (from Spain). I´m going to make an exhibition about Women Inventors, and I need (urgently) the birth and defunction dates of Sarah P Mather. Could you help me please? Thanks a lot.

https://sandrauve.wordpress.com/2015/03/25/women-inventors/

https://sandrauve.wordpress.com/2016/08/29/exposicion-en-biblioteca-francesca-bonnemaison/

When did sarah mather die?