The “Gwinnett” surname is of Welsh origin, first seen in Herefordshire where the family seat was held. The name derived from the Old Welsh nickname “Gwynn” for one who was fairly complected and had blonde hair. The area in Wales known as “Gwynnedd” was home to the family bearing this surname.

Spelling variations of this surname include: Gwinnett, Gwinet, Gwinett, Gwinnet and others. The subject of today’s article, Button Gwinnett, hailed from Gloucestshire. One family historian estimates that the Gwinnett family arrived in Gloucestshire around 1575, leaving the Gwynnedd area of North Wales.

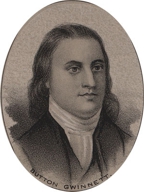

Button Gwinnett

Button Gwinnett was born in Down Hatherly, Gloucestershire, England in about 1735 (at least that is when he was baptized), the son of Reverend Samuel and Anne (Emes) Gwinnett and the oldest of seven children. It is said that he acquired his unusual forename from his godmother Barbara Button. Young Button was educated in Gloucestershire and became a merchant. In 1757 he married Ann Bourne and by 1762 he and Ann decided to immigrate to America.

Button Gwinnett was born in Down Hatherly, Gloucestershire, England in about 1735 (at least that is when he was baptized), the son of Reverend Samuel and Anne (Emes) Gwinnett and the oldest of seven children. It is said that he acquired his unusual forename from his godmother Barbara Button. Young Button was educated in Gloucestershire and became a merchant. In 1757 he married Ann Bourne and by 1762 he and Ann decided to immigrate to America.

The Gwinnett family first landed in Charleston, South Carolina and then continued on to Savannah, Georgia to became a merchant. When his business failed, he sold his stock and purchased St. Catherine’s Island off the coast of Georgia and became a farmer. He turned to politics in 1767, serving as a justice of the peace and later in the Georgia Lower Assembly. After limited success as a planter, Button abandoned politics to concentrate on paying his debts, selling off most of his property, including St. Catherine’s.

It is said that Button had doubts about the colonies succeeding in breaking away from England. After leaving politics he was still active in his community and parish. After coming under the influence of Lyman Hall, Button Gwinnett became an emboldened radical. He was present at Peter Tondee’s tavern in Savannah on July 24, 1774 to debate the right of England to continue to pass laws which were burdensome to the colonists, referred to as “Intolerable Acts”. By 1775 his views had changed and he came out forcefully in favor of the rights of colonists to govern themselves.

It is said that Button had doubts about the colonies succeeding in breaking away from England. After leaving politics he was still active in his community and parish. After coming under the influence of Lyman Hall, Button Gwinnett became an emboldened radical. He was present at Peter Tondee’s tavern in Savannah on July 24, 1774 to debate the right of England to continue to pass laws which were burdensome to the colonists, referred to as “Intolerable Acts”. By 1775 his views had changed and he came out forcefully in favor of the rights of colonists to govern themselves.

In early 1776 he was elected to Georgia’s general assembly in Savannah, which gave him a seat in the national Congress. He traveled to Philadelphia to join other delegates and on July 2, 1776 voted in favor of the Declaration of Independence before it was presented as a “fair copy” to Congress on July 4. On August 2, 1776 he signed his name to the revolutionary document, just above his mentor Lyman Hall:

While serving in the Continental Congress, the opportunity for Button to serve as a brigadier general in the 1st Regiment of the Continental Army arose. However, the position went to his political rival Lachlan McIntosh, embittering Gwinnett. He returned to Georgia and continued to serve in the legislature. In 1777 he assisted in drafting the Georgia state constitution.

In the background he continued to oppose McIntosh, and after Button became president of the Council of Safety, he went even further in his attempts to thwart his rival. To assert his own power Button undertook an attempted invasion of Florida, leading the troops himself. It was an ill-conceived plan and after its failure, Gwinnett was charged with malfeasance. He was cleared of the charges and then ran (unsuccessfully) for Governor.

McIntosh had publicly denounced Gwinnett, and to defend his honor Button challenged him to a duel. They dueled at the distance of only twelve feet and both were severely wounded. However, Button Gwinnett was the only one mortally wounded. He died on May 19, 1977 and was buried in Savannah’s Colonial Park Cemetery. Gwinnett County, Georgia is named after Button Gwinnett.

Today his signature is one of the most rare and sought after of all the signers of the Declaration of Independence. A letter with his signature sold at auction in New York in 1979 for $100,000. By 1983 its value had risen to $250,000.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!