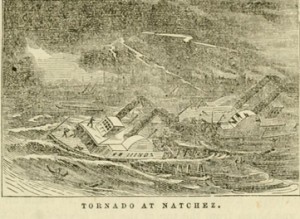

On May 7, 1840 a massive tornado tore through Natchez, Mississippi. Just the night before the area on both sides of the river, Concordia Parish in Louisiana and Adams County in Mississippi, were drenched with over three inches of rain. With all the rain in the area, farmers wouldn’t be planting that day. Nevertheless, the area around Natchez and Vidalia (across the river on the Louisiana side) hummed with activity.

On May 7, 1840 a massive tornado tore through Natchez, Mississippi. Just the night before the area on both sides of the river, Concordia Parish in Louisiana and Adams County in Mississippi, were drenched with over three inches of rain. With all the rain in the area, farmers wouldn’t be planting that day. Nevertheless, the area around Natchez and Vidalia (across the river on the Louisiana side) hummed with activity.

Historically, southwestern Mississippi had been inhabited by Natchez Indians, perhaps as early as A.D. 700 until the 1730’s. Fort Rosalie was established by the French in 1716. With a fort to provide protection from the Indians, permanent settlements began to spring up around the area. There were, of course, conflicts with the Indians, primarily over land use and resources.

On November 29, 1729 the Natchez tribe, joined by the Chickasaw and Yazoo tribes, attacked Fort Rosalie in what came to be known as the “Natchez Massacre.” Over two hundred French colonists were killed that day and the Natchez seized Fort Rosalie. The French retaliated by massacring an entire village of Chaouacha – a group who had nothing to do with the attack on Fort Rosalie. The French, along with Choctaw allies, began a campaign to conquer the Natchez who were then sold into slavery. By the mid-to-late 1730’s the Natchez had been driven away and forced to live with other tribes.

The Spanish and British had a presence in the area, and after the Revolutionary War British claims were ceded to the United States under the terms of the 1793 Treaty of Paris. The Spanish still maintained at least some control until the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, although it took over two years for the Spanish forces around Natchez to receive word. Their surrender came on March 30, 1798 and a week later Natchez was designated as the first capital of Mississippi Territory.

The Spanish and British had a presence in the area, and after the Revolutionary War British claims were ceded to the United States under the terms of the 1793 Treaty of Paris. The Spanish still maintained at least some control until the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, although it took over two years for the Spanish forces around Natchez to receive word. Their surrender came on March 30, 1798 and a week later Natchez was designated as the first capital of Mississippi Territory.

Although the capital was eventually moved to Jackson, Natchez continued to grow and develop into a hub of economic activity, especially the exportation of cotton. The town’s strategic location on the Mississippi River allowed local plantation owners to have their cotton loaded on steamboats at Natchez-Under-The-Hill for transport either downriver to New Orleans or upriver to St. Louis and beyond. Natchez had a burgeoning slave trade market which also contributed to the area’s economy.

On May 7, 1840 there were scores of boats assembled under-the-hill – steamboats, flat boats, skiffs – not just for cotton export but to trade produce and other goods. Just after noon that day a severe thunderstorm moved through the area, accompanied by another round of drenching rain. Simultaneously, about twenty miles southwest of Natchez, a tornado was forming and headed northeast toward the Natchez-Vidalia area.

The tornado roared along the Mississippi, stripping forests and vegetation on both shores. When the tornado reached Natchez Landing, flat boats were tossed into the river, drowning both crew and passengers. Other boats were tossed onto land and those unfortunate enough to be working along the landing area were also killed. Accuweather.com notes that this was the only tornado in United States history where more people were killed than injured – at least 317 were killed and 109 injured.

Some historians believe the death toll was underestimated since during that period of history slaves were possibly not counted. The Natchez Free Trader headlined the tragic event as “Dreadful Visitation of Providence”. The story was picked up by other newspapers, but in many cases news did not reach the rest of the country for days, even weeks afterwards. The Pittsburgh Gazette finally mentioned the devastating storm on May 20 – almost two weeks after the event, and long before the era of “yellow journalism” when headlines would have “screamed” in massive ALL CAPS sensationalism. Oh what a difference one hundred and seventy-four years makes!

Some historians believe the death toll was underestimated since during that period of history slaves were possibly not counted. The Natchez Free Trader headlined the tragic event as “Dreadful Visitation of Providence”. The story was picked up by other newspapers, but in many cases news did not reach the rest of the country for days, even weeks afterwards. The Pittsburgh Gazette finally mentioned the devastating storm on May 20 – almost two weeks after the event, and long before the era of “yellow journalism” when headlines would have “screamed” in massive ALL CAPS sensationalism. Oh what a difference one hundred and seventy-four years makes!

The Free Reader dramatically described the tornado and its aftermath:

About 1 o’clock on Thursday, the 7th inst, the attention of the citizens of Natchez were attracted by an [un]usual and continuous roar of thunder to the southward, at which point hung masses of black clouds, some of them stationary, and others whirling along with under currents, but all driving a little east of north. As there was evidently much lightning, the continual roar of growling thunder, although noticed and spoken of by many, created no particular alarm.

The dinner bells in the large hotels had rung, a little before 2 o’clock, and most of our citizens were sitting at their tables, when, suddenly, the atmosphere was darkened, so as to require the lighting of candles, and in a few moments afterwards, the rain was precipitated in tremendous cataracts rather than drops. In another moment the tornado, in all its wrath, was upon us. The strongest buildings shook as if tossed by an earthquake; the air was black with whirling eddies of house walls, roofs, chimnies [sic], huge timbers torn from distant ruins, all shot through the air as if thrown by some mighty catapult. . . The greater part of the ruin was effected in the short space of 3 to 5 minutes, although the heavy sweeping tornado lasted nearly half an hour. For about five minutes it was more like the explosive force of gunpowder than any thing else it could have been compared to. Hundreds of rooms were burst open as sudden as if barrels of gunpowder had been ignited in each.

Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory, published in 1856, chronicled “Disasters on the Western Waters” and included a story about the Natchez tornado. Although there were always several boats docked in Natchez at any one time, the Steamboat Directory especially noted that: “A tax had recently been laid on flat-boats at Vicksburg, on which account many of them had dropped down to Natchez, so that there was an unusually large number of these boats collected at the last-named city at the time of the tornado.”

The steamboat Hinds was blown into the river and sunk, and all crew members and passengers, except four men, were lost. The Hinds was swept all the way down to Baton Rouge, where it was later found with fifty-one dead bodies – forty-eight males and three females, one of them being a three-year old girl. The steamboat Prairie had just pulled in from St. Louis carrying a shipment of lead. Everything above the deck was swept off and all crew and passengers presumed to have perished. One other steamboat, the H. Lawrence, was sheltered somewhat and although severely damaged was not sunk. One boat, the Mississippian, used as a floating hotel and grocery store, was sunk. Of the one hundred and twenty flat boats at the landing that day, all but four were lost and most of the men who operated them were killed, possibly as many as two hundred.

The Steamboat Directory provided this historical account:

For its violence and destructive effects, this tornado was without precedent in the recollection of the oldest inhabitant of that region. The water in the river was agitated to that degree that the best swimmers could not sustain themselves on the surface. The waves rose to the height of ten or fifteen feet. Many houses in the vicinity of Natchez were blown down, and many buildings in the city were unroofed; the roofs, in some instances, being carried half-way across the river. People found it impossible to stand on the shore. One man was blown from the top of the hill (sixty feet high) and well into the river forty yards from the bank. Heavy beams of timber and other ponderous objects were blown about like straws. Great was the consternation of the inhabitants of Natchez and its neighborhood, and owing to this cause, perhaps, many persons were drowned for want of prompt assistance.

The storm was thought to have been approximately two miles in width since devastation was also seen across the river in Vidalia. While the devastation was immense down at Natchez-Under-the-Hill, the upper part of the city also suffered great damage – hardly a house escaped damage or complete ruin. Homes, hotels and churches were missing roofs or leveled altogether. The Vidalia Court House was “utterly torn down.” While there were many injuries in Vidalia, there was only one fatality. Parish Judge G.W. Keeton was instantly killed while dining with a fellow attorney.

Some citizens were able to make their way to the river and rescue some who were still alive and before their bodies would have been swept down the river. Sorting through the bodies and burying the dead would take some time. In its article, the Free Trader begged the indulgence of their readers while they restored order to their offices. The building was heavily damaged, confusion reigned and residents throughout the city were in shock. The Free Trader summed up the aftermath: “Our beautiful city is shattered as if it had been stormed by all the cannon of Austerlitz. Our delightful China trees are all torn up. We are peeled and desolate.”

The monetary damages were adding up – just days after the storm the Free Trader was estimating at least $1,260,000, close to $30 million in today’s dollars. At that time there was no way to measure a tornado’s strength, but to this day the Natchez storm remains on record as the second deadliest tornado in U.S. history.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks