It’s known by various names – most commonly tuberculosis, but at times throughout history referred to as: “consumption” because the patient experienced severe weight loss and was almost literally “consumed” with the disease; phthisis (derived from Latin-Greek phthinein meaning to waste away); scrofula or Pott’s disease; White Plague (making patients appear pale).

Evidence of tuberculosis has been found in both human and animal remains known to be between 15,000 to 20,000 years old. Egyptian mummies were infected with the bacterium and Hippocrates identified “phthisis” as one of the most widespread diseases of his time, observing that autumn was a particularly bad time of the year for persons with consumption.

Evidence of tuberculosis has been found in both human and animal remains known to be between 15,000 to 20,000 years old. Egyptian mummies were infected with the bacterium and Hippocrates identified “phthisis” as one of the most widespread diseases of his time, observing that autumn was a particularly bad time of the year for persons with consumption.

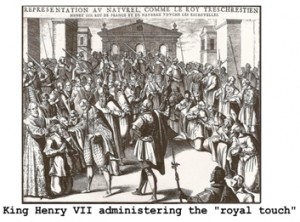

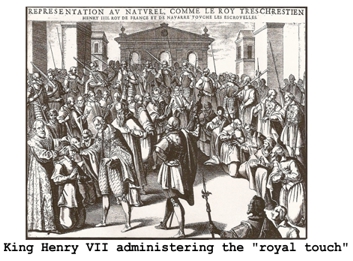

Tuberculosis in the Middle Ages was known as “scrofula” which affected the lymph nodes. Alternatively it was known as “king’s evil” because it was thought to be curable by the touch of royalty. In King Henry VII’s time, the diseased were given amulets or charms to wear that had been “touched” by the King. Charles II may have touched as many as 90,000 victims between 1660 and 1682. By 1712 the practice had declined in England but continued in France until around 1830.

In eighteenth century Europe the disease killed 900 out of every 100,000 persons. Contributing factors were poor sanitation, malnutrition and overcrowded conditions. During this epidemic the disease became known as the “White Plague”. By the next century, it was discovered that the disease was communicable so the idea of isolating patients came about through the use of “sanatoriums”. The first sanatorium was founded in the United States in 1884 by Edward Livingston Trudeau.

In eighteenth century Europe the disease killed 900 out of every 100,000 persons. Contributing factors were poor sanitation, malnutrition and overcrowded conditions. During this epidemic the disease became known as the “White Plague”. By the next century, it was discovered that the disease was communicable so the idea of isolating patients came about through the use of “sanatoriums”. The first sanatorium was founded in the United States in 1884 by Edward Livingston Trudeau.

In isolating patients from society, a sanatorium provided rest, improved nutrition and the chance to recover. These institutions were most widely used before the discovery of either vaccines or antibiotics to treat the disease. Locations in the dry and arid American West were among the most popular because it was thought that drier air was more helpful for the patient than the more humid climes in other parts of the country.

For the wealthy, sanatoriums were set up to run more like what we call a “spa” today. Arizona, and specifically Tucson, was the most popular location – boasting twelve such hotel-like facilities by the early 1900’s. At one point there were so many people who had come to Arizona that tent cities sprang up to house the sick – many sleeping in the open desert. One such location was near what is now central Phoenix, called Sunnyslope, where tents were pitched along the mountainside north of the city.

Quack Cures

Before a vaccine and antibiotic treatments were discovered or widely used, however, there was widespread use of so-called consumption cures or nostrums, or as I like to call them “quack cures”. Given the seriousness of the disease and its characteristic weakening and wasting of a patient, these so-called “miracle treatments” came to be seen as cruel in their promises to cure the diseased.

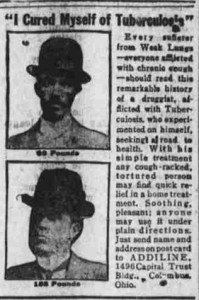

One such cure extensively advertised was “Addiline” and typically the ad would have a picture of a person when they were ill and before taking Addiline, one after taking Addiline and one taken as “latest photo”. Another version of the ad heralded “I CURED MYSELF OF TUBERCULOSIS” – and, of course, it was only available by mail order.

According to the Journal of the Outdoor Life, The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine (December 1920), the usage of Addiline was compared to the foolishness of a child thinking he could catch a bird by putting salt on its tail (Putting Salt on the Germ’s Tail, by Philip P. Jacobs, PhD). Addiline was purported to act as a germicide, in effect overcoming the germs (bacilli). From the Addiline booklet:

Addiline3A laboratory affiliated with the Journal conducted an analysis of Addiline and found it to be comprised of “petroleum oil with a certain amount of pine oil or oil of thyme, possible a mixture of several essential oils”. A leading tuberculosis researcher made the following observation:

The effect of these oils on tuberculosis would of course be fatal . . . In fact it is a great deal like the Frenchman and the flea powder: if you can catch the flea and put the powder on him, you can certainly commit homicide! The same thing might happen to the tubercle bacillus if he should happen to fall into this Addiline oil.

The Ohio State Board of Health did its own analysis and found it to contain petroleum and turpentine oil which essentially cost about 35 cents, but sold for $5.00 – what a profit margin! The Journal referred to Addiline’s composition as nothing more than Russian oil – a common remedy for constipation “or for other diseases that need a powerful and steady cleanser of the bowels”.

The accompanying booklet advised that often after taking Addiline one would experience belching – but not to worry because that was actually beneficial, you see, because that brought the remedy (via vapors) up into the lungs to directly attack the tuberculosis germs! It was the opinion of the Journal that there was no physical possibility for that sort of benefit to be derived. In their opinion, “[L]ong before any such germicidal effect would be experienced, the patient would be in condition for the undertaker.”

The guarantee issued by the Addiline Medicine Company claimed that upon receipt of $5.00 they would send a four-week “trial treatment”. If at the end of four weeks the patient would sign a statement saying no benefit was derived from faithfully following the directions (the company also suggested that the patient follow the practice of good nutrition, adequate rest, etc.), then a refund would be issued. The Journal article pointed out that it was an established fact that tuberculosis patients who were given a so-called cure and strongly believing it to be a cure, would most certainly feel better (psychologically) after taking the treatment.

An experiment had been conducted in New York where tuberculosis patients were intravenously administered a “cure” which really was just milk and water. And lo and behold many patients seemed to recover almost immediately – less coughing and reduced fevers. Eventually organizations like the National Vigilance Committee of the Associated Advertising Clubs of the World began to address the issue of fake advertising in order to give a better impression of advertising as being good and useful for the general public. An analysis done by chemists affiliated with the organization had their own (humorous) conclusion in regards to Addiline: “[I]t would make a better furniture polish than tuberculosis remedy”.

Legitimate Cures

By the end of World War II major medical advances to treat the disease were made when a vaccine known as “BCG” came to be more widely used. In 1944 scientists discovered that streptomycin could be effectively used to treat tuberculosis. In the years following other treatments were developed which led to a significant decline of the disease until the 1980’s when the disease began to experience a resurgence. Contributing to that resurgence was the emergence of HIV and drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis.

Thank goodness modern medicine has better tools today to deal with the disease than a quack cure from the early twentieth century that would have made a “better furniture polish than tuberculosis remedy”.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks