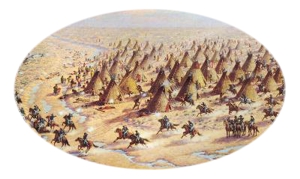

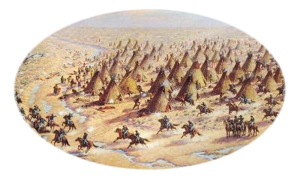

One hundred and forty-nine years ago, on November 29, 1864, perhaps the most atrocious and disturbing attacks in United States military history occurred at Sand Creek, an encampment in Colorado Territory of 700-800 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. The attack was led by John Milton Chivington, a particularly fierce and staunch abolitionist who also happened to be an ordained Methodist minister.

One hundred and forty-nine years ago, on November 29, 1864, perhaps the most atrocious and disturbing attacks in United States military history occurred at Sand Creek, an encampment in Colorado Territory of 700-800 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. The attack was led by John Milton Chivington, a particularly fierce and staunch abolitionist who also happened to be an ordained Methodist minister.

John Milton Chivington

John Milton Chivington was born in Ohio in 1821. John was five years old when his father died, leaving John and his brothers to run the farm. Even though he had only been able to attend school sporadically, by the time he married in 1844 he had been running a timber business for several years. Although not a religious person, he became interested in Methodism and in 1844 he was ordained as a Methodist minister.

In 1853 he worked with a missionary to Wyandot Indians in Kansas. At this time, Kansas and Missouri were embroiled in a de facto civil war over the issue of slavery. John Chivington was a strict abolitionist in pro-slavery Missouri and he ruffled more than a few feathers. Members of his congregation even wrote a letter instructing him to stop preaching.

The next Sunday congregants came to church intending to tar and feather him – Chivington, however, walked up to the pulpit with his Bible and two pistols. He declared, “By the grace of God and these two revolvers, I am going to preach here today”. He soon became known as the “Fighting Parson”. The Methodist Church sent Chivington to Nebraska where he stayed until 1860, when he was named the presiding elder of the Methodist Rocky Mountain District. He moved to Denver, built a church and started Denver’s first Sunday School. It has been said that when he preached his booming voice could be heard three blocks away!

The next Sunday congregants came to church intending to tar and feather him – Chivington, however, walked up to the pulpit with his Bible and two pistols. He declared, “By the grace of God and these two revolvers, I am going to preach here today”. He soon became known as the “Fighting Parson”. The Methodist Church sent Chivington to Nebraska where he stayed until 1860, when he was named the presiding elder of the Methodist Rocky Mountain District. He moved to Denver, built a church and started Denver’s first Sunday School. It has been said that when he preached his booming voice could be heard three blocks away!

When the Civil War erupted the Colorado Territorial Governor William Gilpin offered Chivington a commission as a chaplain, an offer which Covington turned down. He was not interested in a “praying commission” – he wanted a “fighting” commission. In 1862 Major John Chivington, serving under Colonel John Slough, led troops of the Colorado 1st Volunteers on a forced march to Fort Union, covering 400 miles in just 14 days – an astounding feat in that day.

Colonel Slough was ordered by Colonel Edward Canby (Fort Union’s ranking officer) to remain at Fort Union; however, Slough disobeyed orders and headed to Glorieta Pass to engage Confederate forces led by Colonel William Read Scurry and Major Charles Pyron. Initially the battle was somewhat indecisive, but would later turn into a decisive Union victory. The Battle of Glorieta Pass would later become known as the “Gettysburg of the West”.

The Confederates had encamped at one end of the pass near Johnson’s Ranch. After battling for a couple days with the result being somewhat of a “draw”, Colonel Slough ordered a flanking maneuver. Chivington was accompanied by Lt. Colonel Manuel Chaves of the New Mexico Volunteers. Chaves’ scouts had spotted the Confederate supply train encamped at Johnson Ranch so Chivington positioned his troops above the ranch, watching and waiting. After about an hour they began descending to the encampment, surprising the small Confederate force guarding the supplies.

Major Chivington ordered the destruction of eighty supply wagons, some containing flammable liquids and ammunition – horses and mules were also killed. Someone later remarked that Chivington gave the commands with a “perverse glee”. To save bullets, the animals were killed by bayonet. The casualties incurred in the previous days’ battles, and the damage inflicted with the destruction of the Confederate supply train, gave the Union a decisive victory, and Pyron and his troops soon began to retreat back to Texas. Chivington was acclaimed as a military hero.

Chivington returned to Denver where he turned an eye toward politics. A strong advocate for Colorado statehood, he hoped to run for the state’s Congressional seat. Colorado was growing and so too was the conflict between the white man and the Cheyenne. Newspapers helped to fan the flames:

Self preservation demands decisive action and the only way to secure it is to fight them in their own way. A few months of active extermination against the red devils will bring quiet and nothing else will. – Daily Rocky Mountain News – August 10, 1864

That same day, the Weekly Rocky Mountain News endorsed John Chivington for Congress. Blustery as he tended to be, Chivington challenged the territorial governor to decisively deal with the Cheyenne, declaring “the Cheyennes will have to be roundly whipped — or completely wiped out — before they will be quiet. I say that if any of them are caught in your vicinity, the only thing to do is kill them.” A few weeks later Chivington was addressing a group of church deacons and said, “[I]t simply is not possible for Indians to obey or even understand any treaty. I am fully satisfied, gentlemen, that to kill them is the only way we will ever have peace and quiet in Colorado.”

Sand Creek Massacre

In November of 1864, just a few months after speaking out in favor of killing Cheyennes, Chivington led a regiment to the Sand Creek reservation. Earlier Chief Black Kettle had traveled to Fort Lyon to meet with officials and agreed to make peace. He and his group of Southern Cheyenne settled in Sand Creek, assured that they would not be considered hostile any longer by the government. In fact, an American flag and a white truce flag flew over the encampment.Black Kettle_et alBefore Chivington led his troops to Sand Creek many of them had been drinking, further inflaming the situation. Although he observed the American and white truce flags, Chivington ordered an attack on the unsuspecting Cheyenne. After several hours of fighting the death toll stood at somewhere between 150 to 200 Cheyenne massacred, while comparatively only a handful of Chivington’s troops were killed, some reportedly by friendly fire (perhaps due to the drunkenness). Most of the Cheyenne killed were women and children. To add to the horror, many bodies were mutilated and scalped – soldiers cut off fingers and ears for the jewelry and as “souvenirs”.

Initially, Chivington was hailed as a hero and a parade was held in Denver in his honor. But then reports began to surface of drunken soldiers butchering defenseless women and children. Chivington had six members of his regiment arrested and charged with cowardice in battle – the six soldiers had refused to participate in the massacre and were now reporting the atrocities. The Secretary of War arranged their release and ordered them to Washington to testify before Congress.

One of the six, Captain Silas Soule, a close personal friend of Chivington’s, was shot in the back and killed in Denver before he could testify. Court martial charges were eventually brought against Chivington, but by that time he was no longer a member of the military and could not be punished under military law. Criminal charges were never filed either. However, an Army judge summarized it well: “a cowardly and cold-blooded slaughter, sufficient to cover its perpetrators with indelible infamy, and the face of every American with shame and indignation.”

Chivington wasn’t criminally or militarily punished for his deeds, but he was forced to resign the militia and banned from Colorado politics – unable even to participate in the push for statehood. He moved to Nebraska, lived briefly in California and then returned to Ohio to run a small newspaper. He tried politics again in 1883 but withdrew when stories about his participation in the Sand Creek Massacre surfaced. He returned to Denver and served as a deputy sheriff for a short time before dying of cancer in 1894.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks