Today’s surname is easy to identify as to its origins. After the Norman Conquest in 1066 the name appeared as a locational name. The family lived in Leicestershire in a town called “Frisby” (no longer in existence). There is a village in Leicestershire today called “Frisby on the Wreake”, however.

According to one source, there are several towns in England called “Frisby” and all derive from “frisir,” an Old Norman word which meant someone from Frisia or Friesland. The earliest instance of this surname appeared in the Domesday Book of 1086 as “Frisebi” (without surname). In 1198, another “Frisebi,” again without surname, lived in Leicestershire. For the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379, the name “Robertus de Frysby” was recorded and William de Frisseby was the rector of Filby, County York in 1412.

Spelling variations include: Frisbie, Frisby, Frisbee, Frisebie, Frisebye, Friseby and others. At the time of the Revolutionary War there were as many as fifteen spelling variations of this surname.

Richard Frisbie

Records and family histories appear to indicate that Richard Frisbie immigrated to Virginia from England in 1620. It is believed that Richard was born in 1591 in St. James, Clerkenwell, London, England. Most family genealogists believe that Richard married Margaret Emerson on November 30, 1618. In 1619 their first child Mary was born and christened on November 7 in St. James. It seems a bit uncertain as to when their next child, Edward, was born. Some say he was born in 1620 in England and others believe he was born in Virginia in 1621 after Richard and Margaret immigrated there.

What is known is that Richard departed in February of 1620 on board the Jonathan which carried two hundred passengers. The ship reached Jamestown on May 27, traveling fourteen weeks, losing twenty-five passengers and four crew members. One of the casualties appears to have been young Mary (or perhaps she died soon after arrival).

Some family historians speculate that perhaps Richard came over as a half-share tenant of the Virginia Company of London. If so, the terms would have included the Company paying the cost of his passage. In exchange he would have agreed to work for them for a certain number of years and during that time would receive half of what he produced. The crop he raised was likely tobacco.

Some family historians speculate that perhaps Richard came over as a half-share tenant of the Virginia Company of London. If so, the terms would have included the Company paying the cost of his passage. In exchange he would have agreed to work for them for a certain number of years and during that time would receive half of what he produced. The crop he raised was likely tobacco.

Seven years was a common term for an indenture agreement at that time. That would have meant he was bound to the Company until 1627. However, in 1624 the Virginia Company’s charter was withdrawn by King James and placed directly under royal commission. Some speculate that his indenture agreement may have been voided as a result because Richard returned to London in 1625. At this time it appears that he and Margaret had at least two children, Edward and Ann.

Apparently their timing for returning to England was not good as there was a plague epidemic which would sicken Ann. She was buried in August of 1625. Another son, Richard, was born in 1626 and died in 1629. In 1628 twins Zechariah and Henry were born and both died in 1629 (although not the same date). Peter was born in 1630, George in 1633 (died in infancy) and Jane in 1634. It is believed that the family left to return to America in 1635 (Peter, however, was left behind in England for some reason).

There don’t seem to be any more records of Richard, Margaret or Jane. Some speculate they died soon after returning to Virginia or possibly died at sea, leaving fourteen year-old Edward as the family’s sole survivor. Therefore, Edward Frisbie is considered the progenitor of all Frisbies born in America.

Edward Frisbie

Family historians record that Edward, after being banished from the Virginia Colony for his Puritan beliefs, removed to the New Haven Colony in 1644, settling in Branford, Connecticut. Edward married Hannah Rose (or Hannah Rose Culpepper) in Branford in 1649. Eleven children were born to their marriage, including a set of twins:

John – 1650

Edward – 1652

Samuel – 1654

Benoni – 1656

Abigail – 1657

Jonathan – 1659

Josiah – 1661

Caleb – 1666

Hannah – 1669

Silence – 1672

Ebenezer – 1672

All their children lived to adulthood and died in Branford. Some historians have speculated that Edward had more than one wife, but others indicate that Hannah lived until 1690. He was apparently a wealthy landowner since in his will there are references to several tracts of land in Branford. His estate was inventoried on May 26, 1690 – his surname signed as “Frisbye”.

Many of Edward’s Connecticut descendants served in the Revolutionary War. As noted above there were several spelling variations, including: Frisby, Frissbee, Fruisbie, Frisbee, Fresbee, Fresbie, Frisbe, Frisbea, Frisbees, Frisbies and Frisbey.

William Russell and Joseph P. Frisbie

No article about the Frisbie family would be complete without the story of how the round disk known as the “Frisbee” came to be. Historians trace it back to 1871 when William Russell Frisbie moved to Bridgeport from Branford, Connecticut (he, obviously a descendant of Edward). His father Russell operated a grist mill in Bridgeport and William took a job managing the local branch of the Olds Baking Company.

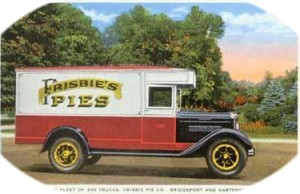

William later purchased the bakery and changed the name to “Frisbie Pie Company”. Upon his death in 1903, his son Joseph took over management of the company. Under Joseph’s leadership the company grew from six routes to two hundred fifty, opening stores in Hartford, Poughkeepsie, New York and Providence, Rhode Island. In his book What’s in a Name?, Philip Dodd describes Joseph’s inventions and management practices:

William later purchased the bakery and changed the name to “Frisbie Pie Company”. Upon his death in 1903, his son Joseph took over management of the company. Under Joseph’s leadership the company grew from six routes to two hundred fifty, opening stores in Hartford, Poughkeepsie, New York and Providence, Rhode Island. In his book What’s in a Name?, Philip Dodd describes Joseph’s inventions and management practices:

The family house became the site of a factory with baking rooms, delivery bays and new machinery, much of it invented by Joseph P., who preferred to custom-design and build his own equipment: a pie rimmer using the principle of the potter’s wheel, meat tenderers, a cruster that could process eighty pies a minute. Since there was no electricity for the bakery, he had a power plant constructed in the basement.

He had high standards of cleanliness and hygiene, a trait learned from his father. The deliverymen in their fleet of trucks and the factory staff wore snappy uniforms, the salesmen crisp jackets with bow ties and peaked caps. They had good wares to sell, up to thirty varieties of individual and family-size pies, delivered hot to a network of grocery stores.

Production levels steadily increased and by 1940 the bakery was churning out two hundred thousand pies a day, employing almost eight hundred workers. Joseph had a heart attack in the 1930’s and in 1941 he passed away at the age of sixty-three. His widow Marion ran the business for several years until it was sold in 1958.

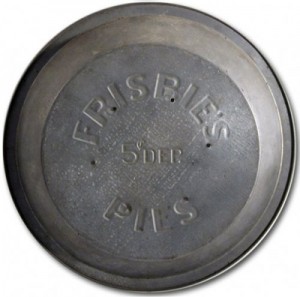

One historian believes that the company’s truck drivers were the first to toss Frisbie Pie tins on the loading docks when they had down time. The tins were engraved with “Frisbie’s Pies” and had six small holes, centered in a star pattern, so that the tin would “hum” as it flew. It is believed that the “sport” of Frisbie migrated to several Eastern colleges, perhaps first at Yale. Students would shout “Frisbie!” to warn of the incoming pie tin – a new sport called “Frisbie-ing” had been invented.

Sometime in the mid-1940’s two men, Walter “Fred” Morrison and Warren Franscioni, saw possibilities in marketing a plastic flying disk. Their first version was called “The Flyin’ Saucer” and wildly popular cartoon character Lil’ Abner was used to sell it. After their efforts failed, Morrison launched his own version in 1955, calling it the “Pluto Platter Flying Saucer.”

That version caught the eye of executives at Wham-O and, as the old saying goes, the rest is history. Wham-O changed the spelling and on January 13, 1957 the Frisbee was introduced to the world. Since 1957 over two hundred million Frisbees have been sold – all attributable to a Bridgeport, Connecticut pie company run by the Frisbie family which could, of course, be traced all the way back to immigrant Edward Frisbie.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks