If you’ve researched Southern slave-holding ancestors, you may be aware of the term “manumission”. If not, it simply means the act of freeing one’s slave(s). As such, manumission differed from emancipation set forth by government proclamation, Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation being a prime example.

Manumission was not a new concept to American slave owners. It’s almost as old as slavery itself. Aristotle thought slavery was quite natural and even necessary. And while there were varying degrees of slavery, all forms limited the Greek slave in one way or another, albeit with a modicum of certain rights extended just for being a human being.

Romulus, the founder and first king of ancient Rome, is thought to have begun the practice in that ancient society by granting parents the right to sell their own children into slavery. Romans would go on to enslave thousands through conquest.

As opposed to Greek slavery, as long as someone was a Roman slave they possessed no rights – none. But, following a slave’s manumission full citizenship rights were extended, including the right to vote.

American slavery was, however, racially-based and transcendent of those ancient traditions. For the American slave owner it was a matter of economics, as set forth in actuarial tables – a sort of justification for at least gradual manumission of slaves – published in The Pennsylvania Packet on January 17, 1774. A “neighboring province” had been recently considered justification for gradual manumission in the last legislative session.1

Virginia passed a law in 1782 following the Revolutionary War allowing slave owners to manumit at will without government approval. In part, perhaps this new law propelled Robert Carter III, one of the state’s wealthiest men, to begin freeing his slaves.

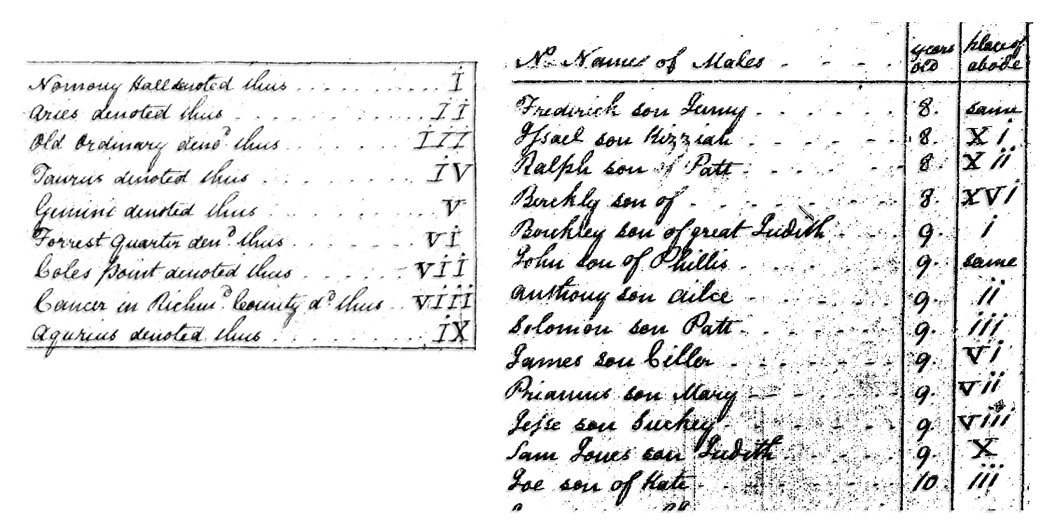

Some have surmised Carter underwent a religious conversion. By signing a Deed of Gift on August 1, 1791 and presenting the same in Northumberland District Court on September 5, he set in motion the gradual manumission of his considerable slave holdings. At the time he enumerated – each one by name and age – over 450 slaves. It is an extraordinary document and thought to have been responsible for the greatest number of slaves freed by one man in all of American history.

He began by providing a table of locations (spread over several counties) where his slaves lived, referencing each named slave with a specific location. He seems to have been intent on crossing all T’s and dotting all I’s.

By the time manumission was completed some three decades later, somewhere between 500 and 600 were thought to have been freed, albeit not without a bit of legal wrangling. In 1793 Robert Carter removed to Baltimore and left the measured and deliberate process in the hands of Baptist minister Benjamin Dawson. When Carter died in 1804 his heirs sued Dawson in order to halt manumission, but lost in an 1808 ruling in the Virginia Court of Appeals.2

This is just one example of the manumission of slaves, something which genealogists with slave-owning ancestors will find interesting. One of the most extraordinary cases occurred in Mississippi, one that was litigated for years before being settled in favor of two manumitted slaves. This article is excerpted from the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase it here.

P.S. Speaking of manumission in Mississippi, there is an interesting story in the February 17, 2026 episode of Finding Your Roots on PBS which featured the ancestry of singer Lizzo. It makes the aforementioned Mississippi case even more interesting since apparently manumission was against the law in Mississippi.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes: