The premise may seem unbelievable, given what our history books have always taught us. It is true – there were free men and women of color who owned slaves. The question is, why would someone previously enslaved choose to enslave others?

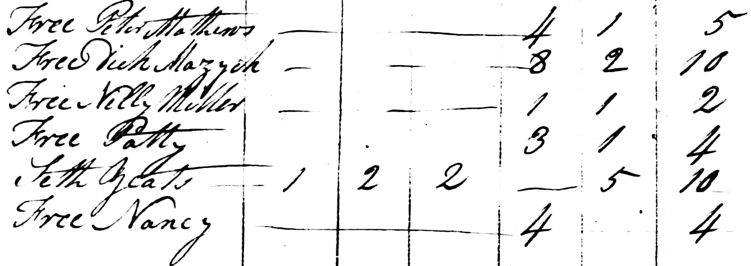

In 1790 in the St. Phillip’s and St. Michael’s Parish of Charleston, South Carolina, a number of free persons of color (male and female) were enumerated as such by “Free” appearing before their given name. A number of these free blacks also owned slaves.

In this particular extracted section, four out of five of the free persons of color owned slaves (next to last column is number of slaves owned), in an aggregate amount equal to the number of slaves owned by Seth Yeats, presumably a white person. According to Larry Koger, author of Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860, there were 36 black slave masters enumerated in Charleston City in 1790. Furthermore, Koger asserts that Peter Basnett Mathews (enumerated as “Free Peter Mathews”) “bought slaves only to emancipate them and asked nothing in return for their acts of benevolence.”1

The slave owned by Mathews in 1790 is said to have been a black man named Hercules, “who was acquired for humanitarian reasons and later emancipated by the colored man.”2 Mathews, a butcher by trade, was one of a number of free black artisans of Charleston who often challenged the societal status quo. He drew attention to South Carolina’s new constitution which provided for Bills of Rights, available to all free citizens, excepting those of the Negro race. Peter, along with another butcher named Matthew Webb and Thomas Cole, a bricklayer and builder, petitioned the South Carolina Senate for redress.

Even though they were free citizens and taxpayers, as well as peaceful contributors to society, they were denied trial by jury and sometimes subjected to “unsworn testimony of slaves.”3 Fifty years after passage of the state’s Negro Act of 1740 which made it illegal for slaves to assemble, raise their own food, earn their own money or learn to write, free Negroes were still being discriminated against simply because of the color of their skin. Not surprisingly, the Senate rejected their petition.

In 1793 Peter Mathews’ home and papers were searched when state officials feared a black uprising. He certainly had nothing to hide and cooperated fully. What sort of papers might Mathews have possessed?

An extensive account of his ancestry (or, at least it seems to be implied) is provided within the voluminous research presented in a two-volume book entitled, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina, From the Colonial Period to About 1820, by Paul Heinegg. Peter Mathews is briefly mentioned at the end of the Matthews family history, perhaps because the author was unsure of just where (or if) in the family line he belonged.

Nevertheless, if Peter was indeed part of this line of free Negroes, the family’s history is believed to have begun with Katherine Matthews, “born say 1668, was a white servant woman living in Norfolk County [Virginia] in June 1686 when she was presented by the grand jury for having a ‘Mulatto’ child. She may have been the ancestor of . . .”4 (followed by a long enumeration of possible descendants). If this assumption is correct, it is possible all of Katherine’s mulatto children were considered free since laws at the time (passed in 1662) stated that a person of color was either free or slave based on the mother’s status.

Peter Basnett Mathews died in 1800 and wrote a will expressing his final wishes in regards to bequeathing what worldly goods he had accumulated to his wife Mary and their children. The opening paragraph indicates his status as a “Man of Colour and Butcher by Trade” There is no mention of slaves, as presumably all he may have ever owned were by then emancipated.

Peter Mathews is just one example. One former enslaved family had the distinction of being South Carolina’s largest slave-owning operation. This article is from the archives, the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase it here.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

- Larry Koger, Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860

(Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1985), 18. - Kroger, 19.

- Stuart Weems Bruchey (editor), Small Business in American Life (Washington, D.C.: Beard Books, 2003 [reprint]), 63.

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina: From the Colonial Period to About 1820 (Baltimore: Clearfield Company, 2005 [Fifth Edition]), 817.