“History in the raw” is how the National Archives refers to “documents – diaries, letters, drawings, and memoirs – created by those who participated in or witnessed the events of the past – tell[ing] us something that even the best-written article or book cannot convey.”1 These historical documents are also among the most valuable resources genealogists can utilize to unravel the mysteries of family history.

“History in the raw” is how the National Archives refers to “documents – diaries, letters, drawings, and memoirs – created by those who participated in or witnessed the events of the past – tell[ing] us something that even the best-written article or book cannot convey.”1 These historical documents are also among the most valuable resources genealogists can utilize to unravel the mysteries of family history.

Locating these historical records is pure “genealogical gold” in many cases. Letters, diaries, journals or memoirs can often go a long way in proving (or dispelling) the various family “legends and lore” – depending on how lucidly (and honestly) one’s ancestor recorded their own history, that is.

According to Merriam-Webster, the word “diary” derives from the Latin word “dies” for “day”.2 The word “diary” is often used interchangeably with “journal”, “journaling” being a common term used today. Either way, these are instruments a person utilizes to record daily events and one’s thoughts and personal reflections.

Like most everything around us, diaries have a history, a long one. One of the earliest references to making regular entries in a diary goes back to the second century when Marcus Aurelius, philosopher and Roman Emperor (A.D. 161-180) recorded “a series of spiritual exercises filled with wisdom, practical guidance, and profound understanding of human behavior”, according to the Amazon.com description.

The first reference to the term “diary” occurred in the early seventeenth century, around the time settlers began arriving on the shores of what one day would become America. Evidence of our forefathers recording their experiences is found in journals, like the one written by William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (1630-1651).

As far as Mayflower history is concerned, his writings, first published in 1854, are considered to be the most complete first-hand account of the Pilgrims’ early years. If you have Mayflower ancestors, find a copy of Bradford’s journal and learn exactly what life was like. In it you will also find the real story of Thanksgiving.

Diaries and journals were more regularly utilized by men in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to record matters related to business concerns. For men like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, keeping a record of daily weather and how it affected their agricultural interests was a vital daily routine. Even when Washington was away from his Mount Vernon plantation he still received a weekly summary of weather conditions. His overseer made sure he received those reports in a timely manner so he could judge how the weather was affecting his crops.

In late January of 1772, George Washington was home and witnessed an epic storm, known now as “The Washington and Jefferson Snowstorm of 1772”, with his own eyes. His weather diary entries read like this:

January 27, 1772, “At home by ourselves, with much difficulty rid as far as the mill, the snow being up to the breast of a tall horse everywhere. Snowed all day. 28 – north wind, very cold, snow drifted in high banks three feet deep everywhere. 29 – Sun shone in morning, but by eleven o’clock it clouded up and snowed all night and then turned to rain.”3

How accurate was George Washington’s account? The Maryland Gazette confirms the observations of the future president:

The Winter here has been in general very mild until Sunday Evening last, when it began to snow, which continued without Intermission until Tuesday Night. Yesterday Morning we had again the appearance of fine moderate weather, but in the Evening it began again to snow very fast, which continued all the Night; ‘tis supposed the Depth where it has not drifted, is upwards of Three Feet, and it is with the utmost Difficulty People pass from one House to another. The Quantity of Snow has also chilled the Water to such a Degree, that though the Frost has been severe for these few Days past, yet our Navigation is entirely stopped up by the Ice.4

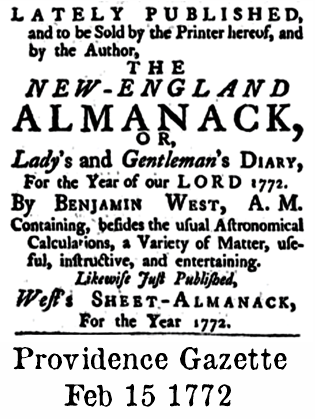

Perhaps Washington used something referred to as a diary which was more like an annual almanac.

Letts of London, founded in 1796 by John Letts, lays claim to this day for publishing the world’s first known commercial diary. In 1812 Letts combined a journal with a calendar, and voilà there was a convenient way to record one’s thoughts on a daily basis, year after year. In the nineteenth century millions of their diaries were sold. The company touted the “Real Value of a Diary”:

Letts of London, founded in 1796 by John Letts, lays claim to this day for publishing the world’s first known commercial diary. In 1812 Letts combined a journal with a calendar, and voilà there was a convenient way to record one’s thoughts on a daily basis, year after year. In the nineteenth century millions of their diaries were sold. The company touted the “Real Value of a Diary”:

Use your diary, we say, with the utmost familiarity and confidence; conceal nothing from its pages, nor suffer any other eye than your own to scan them. No matter how rudely expressed, or roughly written, or with what material, let nothing escape you that may be of the slightest value hereafter, even though it be but to form a simple link in the daily chain of common transactions. If you receive a trivial commission a diary can be more safely entrusted with it than your unaided memory, and one word is often a sufficient memorandum to render it intelligible.5

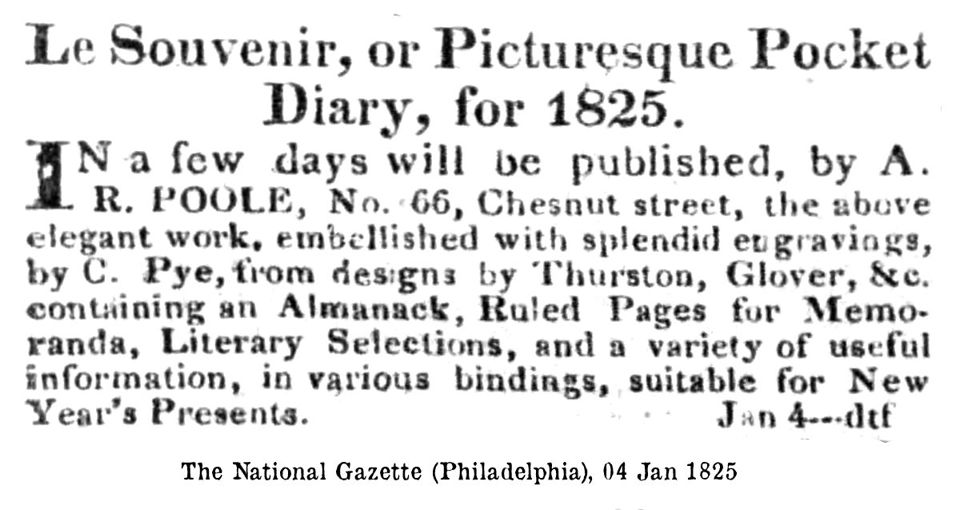

While prior to the 1800s diaries and journals were more often utilized by men, as the price of paper decreased and literacy rates rose, women also began to keep diaries and journals. American stationers began publishing their own version of annual diaries. An advertisement for a “picturesque pocket diary” appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper in early 1825, promoted as a suitable New Year’s present.

Around this time private diaries began to be published, one of the first being the diary of John Evelyn (1620-1706) who wrote of life in 17th century England. The book’s preface lays out the importance of Evelyn’s work (two volumes, over 400 pages), and even the less-than-lofty accounts of any of our ancestors who ever sat down and put pen to paper to record their personal thoughts. It also emphasizes the importance of history in genealogical research:

Of all the aids to a complete comprehension of the political, moral, social, or racial changes, evolutions, upheavals and schisms that make what we call History, the Memoirs of each epoch studied are by far the most valuable. Memoirs may be called the windows of the mind. In the privacy of the boudoir or of the study, men and women will inscribe upon the pages of their journals in terse and unaffected language their real thoughts, motives and opinions, unrestrained by the calls of diplomacy or self-interest.6

Even if you don’t have access to an ancestor’s journals or diaries, you may be able to glean historical context from the pages of a contemporary, someone who lived during a particular era or in the same locality as your ancestor. There are a number of ways to access these types of accounts, especially online. To learn more about those resources and read the remainder of the article, purchase the issue here.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Footnotes:

- “History in the Raw”, accessed on November 28, 2025 at https://www.archives.gov/education/history-in-the-raw.html.

- “Diary.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/diary. Accessed 7 Dec. 2021.

- James Hosner Penniman, George Washington as Man of Letters (Self-Published, 1918), 33.

- Maryland Gazette (Annapolis), January 30, 1772, accessed at www.newspapers.com on December 7, 2021, 2.

- The Bristol Mercury, and Western Counties Advertiser, November 5, 1859, accessed at www.newspapers.com on December 10, 2021, 6.

- John Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn (New York and London: M.W. Dunne, 1901), v (accessed on December 11, 2021 at https://archive.org/details/diaryofjohnevely01eveliala/page/n3/mode/2up).