This year the perennial phrase “Black Friday” seems to me to have invaded the public consciousness rather early. One might wonder what to make of this development. Every year it seems the prospect of Christmas festivities, with its ubiquitous “Black Friday” bargains, is inching closer to being a year-round campaign.

For as long as I can remember “Black Friday” has been associated with the “out-of-this-world” Friday sales following Thanksgiving Day, the day which ostensibly meant a chance for retailers to make a last ditch effort to finish “in the black” before year’s end – no matter how dismally their businesses had performed throughout the year. While residing in California, I looked forward to buying the Los Angeles Times Thanksgiving edition because it was filled with hundreds of “Black Friday” bargains.

While listening to a recent podcast, I learned a bit more of the history of “Black Friday”, which in turn made me curious enough to investigate further. As I often do when tracing the origins of a particular phrase or topic, I first turned to newspaper archives to see just how far back the term “Black Friday” has been used. According to History.com the first “recorded” use of the term was related to a crash of the United States gold market on September 24, 1869:

Two notoriously ruthless Wall Street financiers, Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, worked together to buy up as much as they could of the nation’s gold, hoping to drive the price sky-high and sell it for astonishing profits. On that Friday in September, the conspiracy finally unraveled, sending the stock market into free-fall and bankrupting everyone from Wall Street barons to farmers. 1

- This particular event apparently had far-reaching consequences and remained a topic of discussion for quite some time. Those affected continued to reel from the shock for some time, event to the point of people “scarcely feel[ing] ready yet for pleasure-seeking.”2

- Wall Street will long remember in every bone that termination of the Fiskal [an obvious pun] year which finished up so many with the black Friday.3

- “Black Friday’s” gold operations in New York spoiled several “high-life” weddings.4

One man, a cashier at a Cleveland bank, had at some point embezzled a great deal of money and suffered great loss on that day: “It is estimated that the defalcation of J.C. Buell, Cashier of the National Bank of Cleveland, Ohio, who committed suicide recently, amounts to $400,000, most of which is supposed to have been lost on that ‘black Friday’ in October”.5

According to History.com, the real history of Black Friday only dates back to the 1950s when Philadelphia police coined the term to describe the chaos which ensued on the day after Thanksgiving when the city was flooded with hordes of tourists and suburbanites who rushed to the city in advance of the annual Army-Navy football game held on the Saturday following Thanksgiving ever year. Not only were Philly cops not able to take the day off, but they had to work extra-long shifts dealing with the additional crowds and traffic. Shoplifters also took advantage of the bedlam in stores and made off with merchandise, adding to the law enforcement headache.6

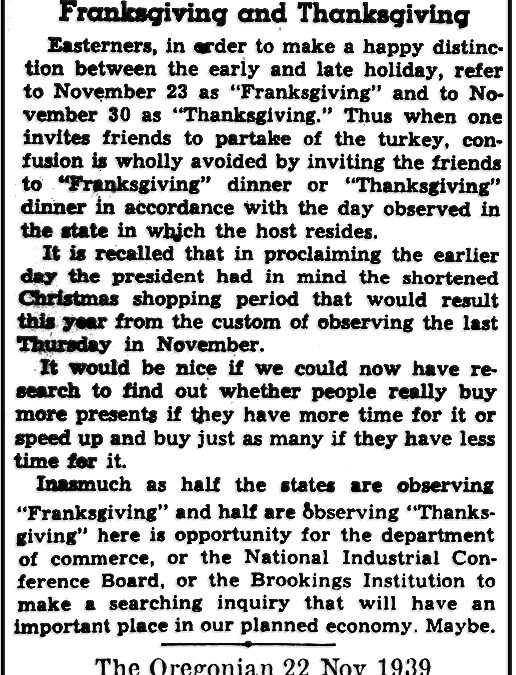

That may very well be true, but several years earlier a cultural shift occurred (or at least an attempt was made), proclaimed by President Franklin Roosevelt in the midst of the Great Depression. His actions caused such a stir that folks derisively referred to it as “Franksgiving”. It makes me wonder if perhaps it may have contributed to the present-day tradition of “Black Friday” (followed by “Cyber Monday” and “Small Business Saturday” – and more).

Historically, an official national day of “Thanksgiving” wasn’t celebrated until the 1860s – while the nation was in the midst of being rent in two. In the mid-nineteenth century, Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, a popular women’s magazine of the era, and author of the children’s poem, “Mary Had a Little Lamb”, began a campaign to unite the nation for one day of annual Thanksgiving. Her idea wasn’t new – it had been around for many years, but the Civil War must have driven her to make a concerted push.

In 1863 Hale wrote President Lincoln, imploring him to make a declaration that Thanksgiving Day should be made “permanently, an American custom and institution.”7 Whether it was Sarah Hale’s letter or Lincoln had already been pondering such a declaration, within one week of receiving her letter Lincoln directed Secretary of War William Seward to draft the declaration, which Lincoln subsequently proclaimed on October 3, 1863:

The year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature that they cannot fail to penetrate and even soften the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign states to invite and provoke their aggressions, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere, except in the theater of military conflict; while that theater has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship; the ax has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battlefield, and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised, nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American people. I do, therefore, invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a Day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens. And I recommend to them that, while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation, and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes, to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility, and union.8

Every year thereafter each successive president decreed the last Thursday in November as a national day of Thanksgiving – that is, until President Franklin D. Roosevelt, perhaps in response to the nation’s continuing economic struggles, proclaimed that Thanksgiving would be moved up one week. Why? So that retailers might have one additional week between Thanksgiving and Christmas – to potentially “finish in the black” by year’s end.

It appears Roosevelt had been pondering the idea for some time. In 1933, the first year of his first term in office, November had five Thursdays. Under pressure from retailers to provide them some relief by allowing more time for customers to shop for Christmas, he considered their proposal, but didn’t actually act on the idea until 1939 when November again had five Thursdays. Was he about to launch yet another “FDR experiment”?

On August 14, 1939 he announced his intentions at a Campobello Island press conference. After being peppered with a number of questions ranging from the current “international situation” to matters of domestic concern, near the end of the press conference the press was practically begging for a headline. After replying, “I haven’t got a thing”, Roosevelt suddenly came up with a “swell story” that he had entirely forgotten:

On August 14, 1939 he announced his intentions at a Campobello Island press conference. After being peppered with a number of questions ranging from the current “international situation” to matters of domestic concern, near the end of the press conference the press was practically begging for a headline. After replying, “I haven’t got a thing”, Roosevelt suddenly came up with a “swell story” that he had entirely forgotten:

I have been having from a great many people for the last six years, complaints that Thanksgiving Day came too close to Christmas. Now this sounds silly. In other words, between Labor Day, which is generally observed, and Christmas, there is too long a gap up to Thanksgiving Day when it comes at the very end of November, and there is a great long gap even for those states that celebrate the twelfth of October, Columbus Day. The stores and people who work, retail people, etc., are very anxious to have it set forward and I checked up and it seems to be the only holiday which is not provided for by law, nationally, even though it may be in a small number of states. In most states it is a Governor’s Proclamation. This year, because Thanksgiving Day is the thirtieth of November, I am going to step it up a whole week and make it not the last Thursday but the Thursday before the last Thursday in November.9

He explained that “in the early days of the Republic, it was held sometime in October, being a perfectly movable feast, and it was not set as the last Thursday in November until after the Civil War, so there is nothing sacred about it, and as there seems to be so much desire to have it come a little earlier, I am going to step it up one week.”10

Well, the press got their headline – and the public’s response was swift, and generally disapproving, at least initially. Newspapers across the nation were filled with quips and jabs at Roosevelt’s audacious proposal:

A Kansas newspaper comes near daring F.D.R. to call it Franksgiving.11

From Plymouth, Massachusetts: James Frasier, chairman of the selectmen of this historic town where Thanksgiving day was first observed, said Monday night he “heartily disapproved” President Roosevelt’s plan to proclaim the holiday a week early.12

SOME GOVERNORS MAY BALK AT ROOSEVELT’S ACTION IN CHANGING THANKSGIVING DAY13

We are strongly opposed to any change that may be made from the regular Thanksgiving Day custom and feel we would be sacrificing the real significance of the day for the purpose of satisfying commercial interests.14

Calendar Men Are Upset at F.R. Thanksgiving Plan – President Roosevelt’s announcement that he was advancing Thanksgiving Day a week today threw consternation into the ranks of calendar makers. . . [one businessman complained,] the date changing would “raise hell” with his business and cost calendar makers from $5,000,000 to $10,000,000.15

On and on the complaints and jabs kept coming, and within days the term “Franksgiving” began appearing in headlines and news items around the nation:

From the Centralia (Washington) Chronicle: Franksgiving Day is Nov. 23 – Thanksgiving day will remain the last Thursday in November.16

It appears a number of localities took this stance, but that didn’t stop the chatter around what many Americans considered a huge cultural shift. No doubt, the date change presented challenges for some annual family gatherings and reunions, such as planned festivities for the Harlin family of Waurika, Oklahoma, whose son had “Franksgiving” day off, but his wife, a librarian, had scheduled their vacation on the “old fashioned date”.

It appears a number of localities took this stance, but that didn’t stop the chatter around what many Americans considered a huge cultural shift. No doubt, the date change presented challenges for some annual family gatherings and reunions, such as planned festivities for the Harlin family of Waurika, Oklahoma, whose son had “Franksgiving” day off, but his wife, a librarian, had scheduled their vacation on the “old fashioned date”.

By the time it was all over, however, some folks had come around to liking the idea after all. On December 28 it was reported that a Nebraska hardware man had bemoaned “the dual turkey day proposition . . . but admitted ‘Franksgiving’ was a good idea.”17 Merchants of Columbia, Missouri had to admit “Franksgiving” had actually been quite beneficial. In fact, a delayed Thanksgiving would have considerably hurt their business. Still, however, the complaints and jabs continued.

Roosevelt had initially received telegrams and letters, pro and con, some expressing concern while others praised his actions. The New York Times had gone so far as to issue a special release, stating that the president had “turned a deaf ear to pleas of retail merchants and other trade organization.” Surely the date change “would cause considerable confusion”, as well as “disarrange football games which are scheduled for Thanksgiving and interfere with railroad excursions at that time.”18

The debate raged again the following year as some states proclaimed Thanksgiving for the third Thursday of November, while others fell back to the traditional fourth Thursday. Roosevelt’s declaration, after all, wasn’t legally binding. In Texas the debate was settled by setting both dates as government holidays. In 1940 and 1941 November had the customary four Thursdays and Roosevelt once again declared the third Thursday as Thanksgiving as the third Thursday. Another round of political and societal dust-ups occurred yet again. By late 1941, however, both houses of Congress had their fill of the controversy, passing a bill to officially set aside the fourth Thursday in November as Thanksgiving Day.

At least, Roosevelt never followed through with another idea his administration concocted – changing the date not to the fourth Thursday but rather the “Monday nearest the fifteenth of November.” In response, the Washington Federation of Churches, which had gotten wind of the idea, forwarded a message to the President’s office: “The Protestants will raise ‘Hell’ if you change their Thanksgiving Day celebration from Thursday to Monday.”19

In lieu of moving Thanksgiving up one week, as Roosevelt chose to do during challenging economic times, might the current designation of the Friday after Thanksgiving Day being called “Black Friday” be a compromise of sorts, keeping everyone happy? Wishing everyone who chooses (or dares) to participate a happy “Black Friday” shopping day!

SPEAKING OF BARGAINS, Digging History and Digging History Magazine has one of its own, a special “10-10” promotion. See the details here: digging-history.com/dhmpromo/

- “What’s the Real History of Black Friday?”, accessed on November 21, 2025 at https://www.history.com/articles/black-friday-thanksgiving-origins-history.

- The New York Times, October 7, 1869, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 21, 2025, 1.

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis), October 23, 1869, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 21, 2025, 2.

- The Yonkers Gazette, November 6, 1869, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 21, 2025, 2.

- Los Angeles Star, December 25, 1869, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 21, 2025, 4.

- “What’s the Real History of Black Friday?”, accessed on November 21, 2025 at https://www.history.com/articles/black-friday-thanksgiving-origins-history.

- Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia), November 27, 2024, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 21, 2025, A002.

- “Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of Thanksgiving”, accessed on November 21, 2025 at https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/abraham-lincolns-proclamation-thanksgiving.

- Press Conference Transcript, August 14, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/pc/pc0085.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Toledo Blade, August 26, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.genealogybank.com, 4.

- The Des Moines Register, August 15, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.newspapers.com, 1.

- The Scranton Times-Tribune, August 15, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.newspapers.com, 1.

- The Sacramento Bee, August 15, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.newspapers.com, 4.

- The Oakland Tribune, August 15, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.newspapers.com, 11.

- The Indianapolis Star, September 26, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.newspapers.com, 8.

- Cedar County News (Hartington, Nebraska), December 28, 1939, accessed on November 21, 2025 at www.newspapers.com, 3.

- G. Wallace Chessman, “Thanksgiving: Another FDR Experiment”, accessed at https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/fdr-thanksgiving-experiment#nt1 on November 21, 2025.

- Ibid.