The first use of barbed wire in Texas occurred in 1857 when immigrant John Grinninger ran homemade barbed wire along the top of fencing around his garden. The first United States Patent for barbed wire was issued in 1867.

The first use of barbed wire in Texas occurred in 1857 when immigrant John Grinninger ran homemade barbed wire along the top of fencing around his garden. The first United States Patent for barbed wire was issued in 1867.

Barbed wire began to be mass-produced after another patent was granted to Joseph Farwell Glidden of Illinois. Prime range land consisted of treeless stretches of prairie. Without significant supplies of timber to build fences, barbed wire became more popular as cattle ranchers sought effective means to control access to their land.

The XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle put up some six thousand miles of barbed wire and farmers would fence their grain fields as well. Sometimes the fencing crossed roads and interfered with delivery of the mail — even public land was fenced. Open range cattle ranchers became alarmed when access was cut off to prime grazing pastures and water.

The XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle put up some six thousand miles of barbed wire and farmers would fence their grain fields as well. Sometimes the fencing crossed roads and interfered with delivery of the mail — even public land was fenced. Open range cattle ranchers became alarmed when access was cut off to prime grazing pastures and water.

The situation reached a crucial stage in 1883, a year of severe drought. News and opinion articles across the state highlighted the work of the “nippers” as they were called. According to Texas, A Modern History: Revised Edition (p. 92):

Nipping became indiscriminate and was often done secretly at night by armed groups calling themselves Owls, Javelinas, or Blue Devils. They threatened fencers and burned pastures. Three people died and damage was estimated at $20 million.

The Galveston News reported that nippers had destroyed fencing around a 700 acre property on Tehuacana Creek near Waco. A threatening note regarding a pond on private property was left behind:

The Galveston News reported that nippers had destroyed fencing around a 700 acre property on Tehuacana Creek near Waco. A threatening note regarding a pond on private property was left behind:

You are ordered not to fence in the Jones tank, as it is a public tank and is the only water there is for stock on this range. Until people can have time to build tanks and catch water, this should not be fenced. No good man will undertake to watch this fence, for the Owls will catch him. There is no more grass on this range than the stock can eat this year.

While newspapers were vocal in their condemnation of nipping, state politicians were mostly silent on the issue. Meanwhile, however, Governor John Ireland was being urged to intervene. One of the strongest lobbyists for intervention was a woman by the name of Mabel Doss Day.

In 1881 her husband had died after his horse fell during a stampede, leaving his widow with a debt-ridden ranch. She successfully worked to put the ranch company back on solid financial ground and in 1883 her land was the largest fenced ranch in Texas. Mabel became a victim of the fence cutters and lobbied in Austin for a law to make it felonious to cut fencing. A special legislative session was called by Governor Ireland to meet on January 8, 1884 to craft a solution.

After weeks of debate, the legislature passed a bill that made the crime of fence-cutting punishable by one to five years in state prison, while the crime of burning a pasture was punishable by two to five years in prison. It became a misdemeanor to willfully and knowingly fence public lands or someone else’s property without consent. Offenders had six months to comply with the new law, and for fences that crossed public roads, gates were required every three miles.

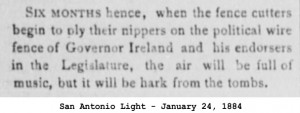

The law apparently wasn’t necessarily popular state-wide:

And, the law didn’t necessarily solve the problem either. It appears that the crime of “nipping” continued for years (click to enlarge):

Drought years would heighten nipping activity even after the law’s passage, until in 1888 local law enforcement in Navarro County called on the Texas Rangers to intervene. Sergeant Ira Aten (who would later be instrumental in settling the Jaybird-Woodpecker War) and Jim King were dispatched to the area. Disguised, the two Rangers secured jobs picking cotton and kept their eyes and ears open, soon discovering who the cutters were. Aten placed dynamite charges along fence lines so that when the wire was cut an explosion would occur. While the Adjutant General did not approve and ordered the practice to cease, fence cutting was curbed significantly and eventually the Fence Cutting War subsided.

Is the line drawing of longhorns behind t barbed wire fence copyrighted?

Thanks

That I’m not sure of. I’m in the process of digitizing the web site and for articles I may use in the new magazine format I am attempting to diligently determine ownership of images and receive permission where needed. I have misplaced my original sources for this article and I’m not finding it anywhere online with a source. If I’m unable to find the origins of the drawing I will not use it for future publication and even the little clipping on the Digging History blog will eventually be taken down. I’m finding when possible it’s much easier to use images in the public domain (and of course cited as such). Were you hoping to use the image?